My father was posted to the Middle East (and East Africa) during the war and wrote to his mother as regularly as he could – usually once a week. His mother kept all the letters and they must have been passed back to him. We found them when we were clearing out my mother’s house and I remember her saying, years before when I had asked what the parcel was, that she had meant to read them but never got round to it. I took them, with the intention of reading them, but have only just got round to doing so and only now because my brother said he would be interested in seeing them!

My father’s writing was always hard to read, being mostly a straight line with a few bumps in it! It was like that even in 1940 so the enterprise of reading a letter a week from about September 1940 to about February 1945 is quite a major task. I also decided it might be best to summarise each letter, with notes, to make it easier to find specific passages or events. As all place names were either left out or censored I have also used the internet and the photos he took (which I also have and were labelled, probably later) to try to work out where he was and what he was doing.

The letters are mostly written on flimsy air mail paper, on both sides and many of the early ones in pencil. At some stage his elder sister must have suggested that his writing was clearer when in ink, because he replies that the army did not always provide the facilities to carry ink! Some of the descriptions of the places they were in, including a place where they were not even provided with tents, suggests why.

I have read less than a year so far, but it is interesting to see how the letters are almost always positive – but that was probably because he was writing to his mother and didn’t want her to be worried.

He was called up in summer 1940 when he was 24 and did basic training in Plymouth, I gather.

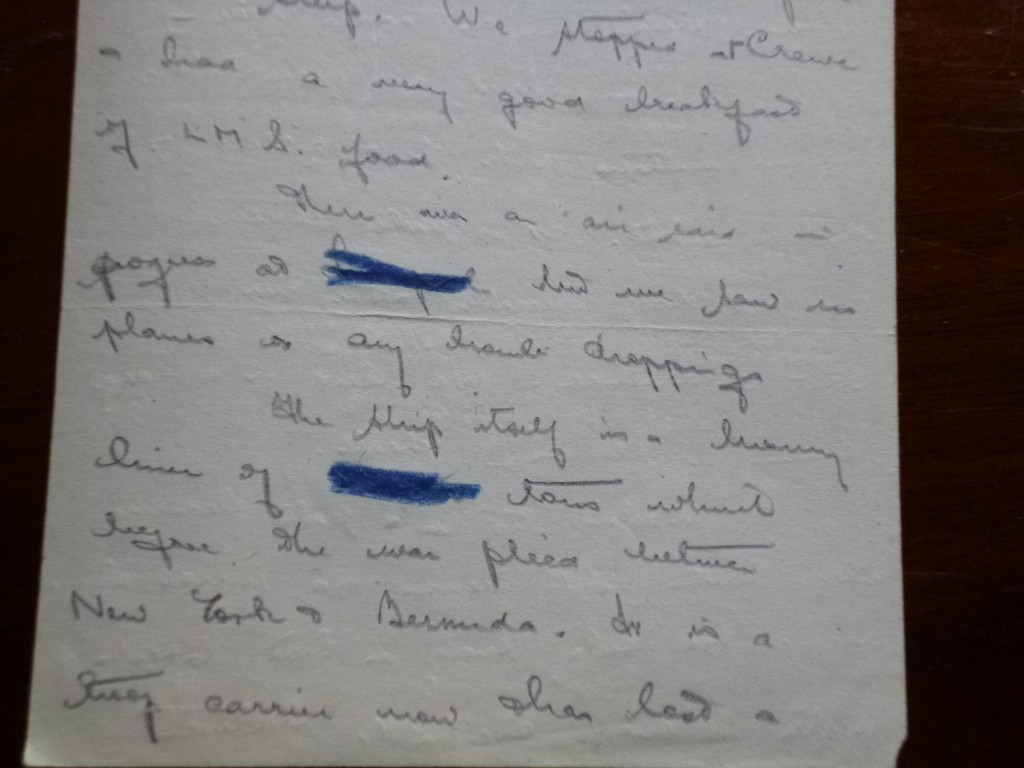

They sailed from Liverpool and he was in an ex-luxury liner (see letter above) that had been modified as a troop carrier. They hit a gale and he was somewhat smug at not getting sea-sick, like most people. Their first port of call was somewhere in West Africa, probably Freetown and then they stopped at Cape Town, which they were allowed to mention. Most of the letters are descriptions of what he has seen, describe the daily routine and sometimes even the food. On the ship out this was initially good, but I think it went down a bit after they had been at sea longer.

From South Africa they sailed to, I think, Suez and spent some time there doing further training and acclimatising to the heat. There are descriptions of everything he saw, which are very interesting at times. They went from there to what I think was most likely Sudan. Near the start of December he got dysentery and malaria and was sent to hospital, almost certainly in Khartoum. There was a gap of almost a month in the letters because of that. The cure for dysentery was starvation diet (!) and quinine for malaria. He was about another 3 weeks recovering before being sent back to his regiment.

There had been much frustration at not getting any letters but the first – dated October 20th 1940 – arrived mid-January 1941. For a while they then seemed to arrive – irregularly, but enough so he knew things had been OK at home (several months before). He was obviously very fond of my cousin Gavin and usually asked how he was, if he has started school or comments on his pictures or letters that had been sent.

I think he was then on the Sudan-Eritrea boarder, living in straw/mud huts and doing further training, including a 75 mile route march in 6 days. He found “life hardly enjoyable but not quite intolerable”.

Near the start of March they moved again, I suspect into Eritrea and were living out with no tents, and for a while not much water either. Someone invented a shelter by supporting a blanket on poles cut from the trees, which had been their only protection from the sun, prior to the improvised shelters. They were doing further training up in the mountains. It is at that stage that he says: “a good cook is a man with a sharp tin opener”!

There is then a gap in the letters of about a month. As this coincides with the Battle of Keren this suggests this is what he was involved in. There is also a photograph labelled “Near Keren – the “road block” ” which wikipedia mentions. The photograph must have been taken about 2 months later as he did not get a camera until about then.

He says he had 16 bad days – lack of sleep, shortage of water, intense heat, filth but he was alive and now feeling quite “chirpy”. They had travelled in gradual stages to Asmara and he had been made temporary company clerk. He stayed in Asmara for about 2 months and after about 2 weeks had been moved to train as a cypher clerk, as a temporary measure, initially. He comments that it is “a job to which I am more suited. I shall never be any use as an infantry soldier”.

While in Asmara he moved “barracks” several times and bought both a watch and a camera. He had his photograph taken professionally so that he could send copies home – and was surprised to find a copy up in the photographers to act as an advertisement.

I just love the leopard skin on the floor! Note the pipe – which we always knew him to smoke – and the moustache which is new from the photos taken before he left Britain. One of his sisters must have asked about it as he comments in one of his letters that he has not decided what shape to have it. It was still there when we were young, but it was shaved off when it went grey. It was at this stage that he only weighed 8 stone 5 lbs and says he is half a stone heavier than he was 6 weeks before (!!!), mostly because of the dysentery. He did start to put weight on again in Asmara because working as a cypher clerk he had time to look round the town and spend time in the cafes where he enjoyed pork, ice-cream (Italian?), cream buns and sponge cake among other things.

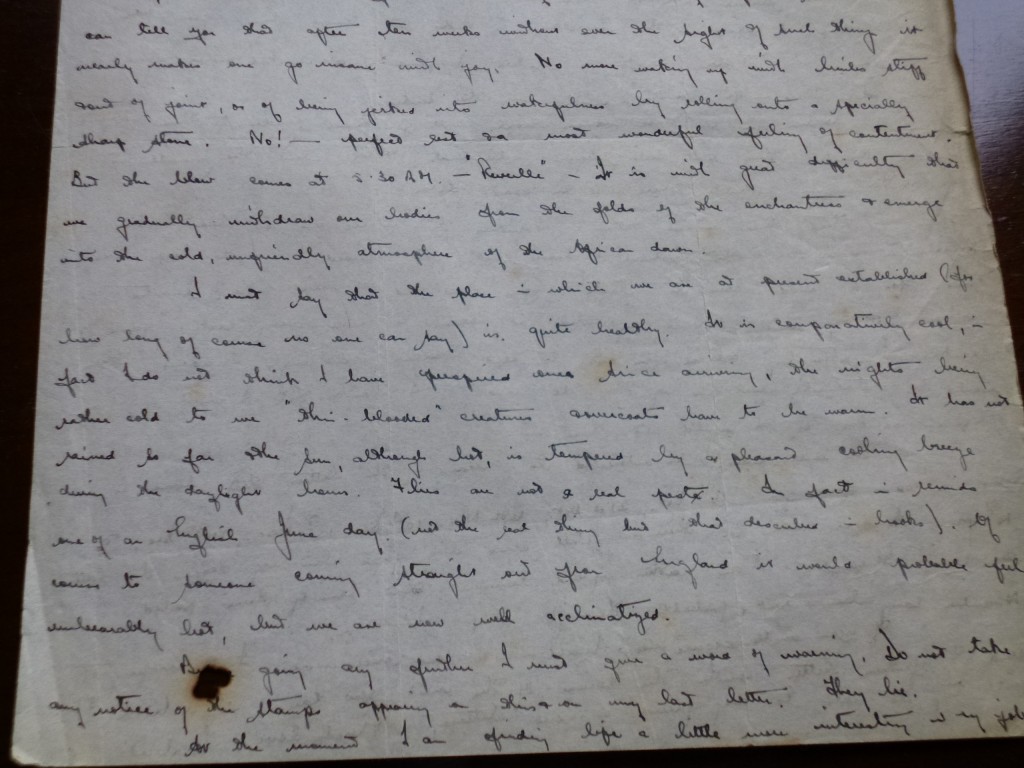

If you can read the letter it is commenting on the climate in Asmara, which is comparatively cool as it is over 7500 ft above sea level. After the 2 months in Asmara, he was sent on a course to learn more about cyphers. This involved 3 trains and 2 trucks to get him to Khartoum, where he was told he was to stay for a while before going on the course. He gains more experience of cyphers work as he is waiting there. He found the weather extremely hot and experienced at least 2 sandstorms, which are described and sound very unpleasant! He was living in a transit camp and mentions the large number of nationalities of soldier who passed through, but this was a bit of a strain, I think, as communication was mostly by sign language. Just before he went on his course he was moved into some much more comfortable accommodation.

After 6 weeks in Khartoum he was sent on his course. This involves another journey of several days, involving a train – partly across what I assume is the Nubian desert – a boat trip down the river and then two more trains. His description of the desert is:

“Boring is not the word. It is ten times worse. Sand, flat, with an occasional low rocky range of hills, not even a cloud to break the monotony. The colouring is magnificent, if elementary. The dazzling sunlight reflects a brilliant yellow, contrasting sharply with the vivid and deep blue of the sky. Red (brick colour at the stations), yellow and blue are the only colours to see all day. It is a terrific strain on the eyes. How true that green is a soothing colour and how we long to see it again (shan’t I treasure the lovely English greens when I return home).

“Night falls and the blue turns to a dense black through which myriads of stars twinkle. The sand merges into the sky and we rest again and thus arrive at the end of the first part of our journey.”

He ends up in Egypt and in a city which he initially finds very noisy after the places he has been. This was Cairo, as evidenced by his mention of “The Victory Tea Rooms”, which I located through an internet search. He does his course and is then employed locally, where he enjoyed the food, the facilities (including the chance to watch cricket!), but has to wage a constant war against (bed?) “bugs”, which are not only in the accommodation but everywhere – the office, cafes …. He was sleeping outside on the roof, as this reduced the number of bites from the bugs, although there were still some bugs in the blankets. At the end of August 1941 he was promoted to sergeant.

On the whole, reading these is interesting, if hard work. The descriptions of places are quite good and I recognise some of the sort of things described from my time in Kenya. He does well to describe what he is doing within the limits of the censor. I get the impression that he appreciated the chance to travel and see places, but on the whole would have liked to go home! He was happiest in places where there was a good supply of books, newspapers and periodicals, such as Khartoum and what I think is Cairo. He also was getting quite well fed in these places and was concerned that his mother should not send him things like cakes, as she needed the food more than he did. I get the impression that he didn’t make that many friends and was happiest when he could spend the time reading – or watching cricket, of course!

You never know he might have met my granddad while he served in the same places.

But we will never know as Dad’s letters only give first names of friends. Was your granddad in the West Yorkshire Regiment, too?